The General Workers’ Union (GWU) said its proposal for a pilot four-day week project is not just about reducing working hours but about reimagining the world of work itself.

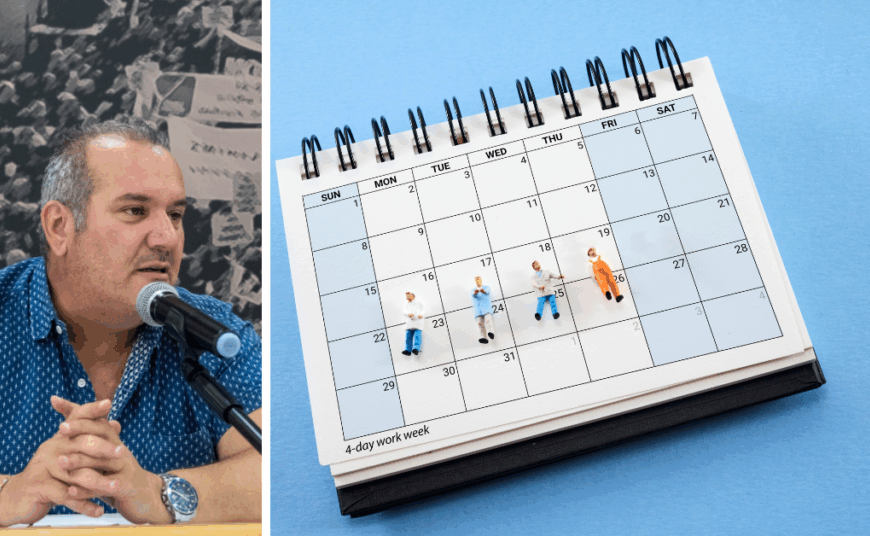

After the GWU called for a pilot four-day, 32-hour week in both the public and private sectors, the union’s secretary general Josef Bugeja spoke to Lovin Malta about the rationale behind this proposal.

This proposal marks an evolution from the union’s call a few years ago for workplaces to give employees the option to work their regular 40-hour shifts over four days rather than five.

“In 2023, we proposed introducing flexible working arrangements in response to the growing challenge employees face in reconciling work and family commitments,” Bugeja said.

“Our proposal focused on a 40-hour work week spread over four days.”

“Last year, we took this idea further by proposing a study on the feasibility of a 32-hour work week. This year, we advanced the concept by recommending both a study and a pilot project to collect data and evaluate the potential of such an initiative.”

The initiative is based on the ‘100-80-100’ principle: maintaining 100% productivity in 80% of the time, with 100% pay.

Josef Bugeja with Prime Minister Robert Abela (Photo: GWU)

Bugeja said the pilot project should measure the impact of a four-day week on Malta’s competitiveness, productivity, efficiency, service costs, service quality, and most importantly worker well-being.

“It is important to emphasise that we never called for the immediate introduction of a 32-hour work week,” he said.

“Our proposal is for a structured, evidence-based process to assess feasibility, measure impacts, and identify ways to mitigate any adverse effects.”

“With technological progress, innovation, and artificial intelligence transforming the world of work, it is crucial to understand how these changes can support new, smarter ways of working.”

He noted that similar pilot projects are already underway in a number of countries, such as Portugal, Spain, Poland, the United Kingdom, Finland, Belgium, Germany, and Iceland.

“Given that we operate within a global economy, we have also stressed that such measures cannot be taken in isolation. This must be part of a broader, international discussion on the future of work,” he said.

The GWU hasn’t earmarked any specific companies or government departments which should form part of the pilot project, stating that the selection process should form part of the study itself.

“The goal is to gather reliable data and gain a clear understanding of the impact across different sectors,” he said.

Photo: GWU

While he acknowledged that certain industries – particularly healthcare, retail, and hospitality – present unique challenges, he said they may require careful scheduling adjustments, additional hiring, or innovative shift patterns to maintain service levels.

“This is precisely why a study and pilot project are essential: to identify what works, what doesn’t, and how solutions can be tailored to different realities,” he said.

“It is fundamental that a 32-hour working week without loss of pay cannot be viewed or understood as simply a reduction in working hours.”

“It’s about reimagining how work is organised in a way that reflects technological progress, supports environmental sustainability, and responds to human needs.”

“Global evidence increasingly shows that, when well-designed, such systems can deliver strong results—not only for workers, but also for businesses and society as a whole.”

Asked whether he envisages a future where all workers benefit from a four-day week, Bugeja said that such pronouncements would be premature until hard evidence is obtained.

“Any decision must be based on facts and data, not assumptions or ideology,” he said.

“This initiative is not simply about reducing working hours—it’s about reimagining the world of work itself.”

“When the 40-hour week was first introduced, I’m sure similar debates took place. Yet history shows that progress in working conditions has always come from adapting to social and technological change.”

“If today’s world of work is being reshaped by technology and artificial intelligence, then we must also have the courage to rethink how work is organised and performed.”

“In trials conducted abroad, overall productivity often remained stable—or even improved—while employee well-being saw significant gains. That is exactly the kind of evidence we need to examine before considering how such a model could apply across different sectors and if it is possible to adopt it.”

Bugeja added that the proposal cannot be considered in isolation, and that Malta requires a 360-degree view of the labour market.

“A few years ago, few imagined that digital platforms would become major employers — yet today they are.”

“So we must also ask: could this proposal help address Malta’s demographic challenges? Could innovation and artificial intelligence serve as the pivot for a more efficient, balanced workforce?”

“And could it help tackle the growing mental health challenges faced by many workers? There are many important questions that can only be answered through serious research, data collection, and evidence.”

“Ultimately, introducing a 32-hour work week without loss of pay is not just about cutting hours — it’s about rethinking how we work. It should be studied in depth, tested through pilot projects, and discussed openly between social partners.”

“We see this not as a risk, but as a strategic investment — one that can strengthen Malta’s workforce, enhance competitiveness, improve efficiency, and promote well-being.”

“It is a forward-thinking initiative that embraces innovation not only in technology, but also in how we define the very value of work and working time.”